Juliana Koh ◈

General donors’ behaviour needs and motivations for giving have been well-researched. Most of the studies focus on forces that drive charitable giving, and these are typically classified under donors related, charity, internal and external motivators, and affect, behavioural and cognitive aspects of motivators (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011; Degasperi & Mainardes, 2017; Kumar & Chakrabarti, 2023).

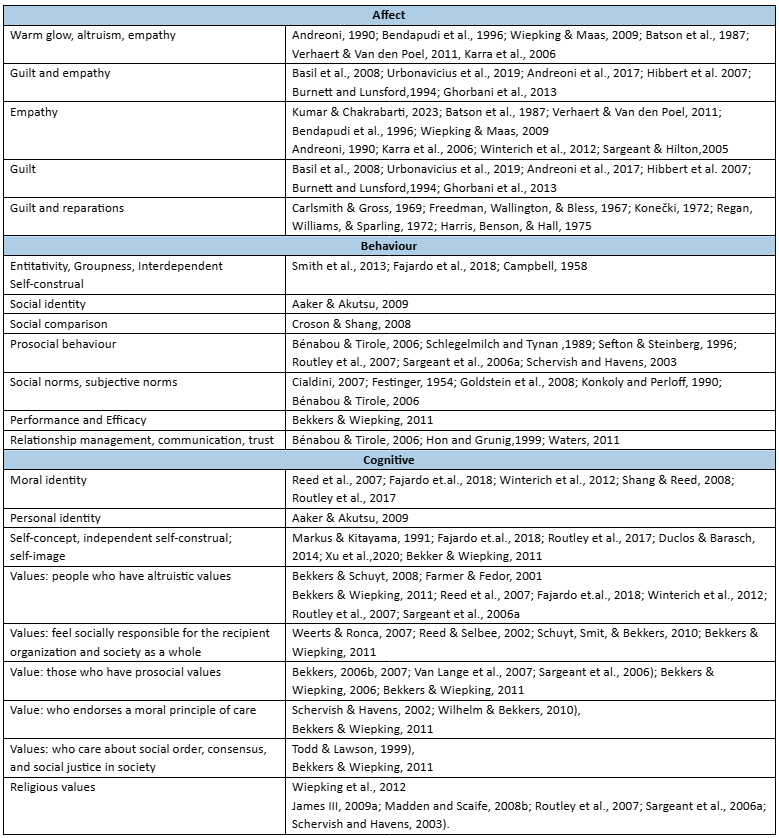

Emotionally, donor’s giving may be motivated by of seeking of feeling the warm glow, altruism, empathy, guilt and reparations. Maintaining of social norms, exhibiting prosocial behaviour, social comparison and peer pressure also drive giving. And at the core of giving, donors are motivated by values: personal values, altruistic values, values of feeling socially responsible for society and recipient organisation, prosocial values, social justice and religious values. A study by Bekkers & Wiepking (2011) consolidated these into eight factors by the process from trigger to action of donation: awareness of need, solicitation, cost/benefit, altruism, reputation, psychological benefit, values, and efficiencies. Table 1 shows the range of donor’s motivations put together by the Affect, Behaviour, and Cognitive (ABC) of giving.

Table 1: Affect, Behaviour, Cognition (ABC) Drivers to General Donor’s Giving

For the area of charitable bequest, in addition to domains of marketing, consumer behaviour, non-profits and volunteering, sociology, psychology, social psychology, and economics, charitable bequest literature spans studies on will, inheritance, charitable bequest, general donor behaviour, philanthropy, fundraising, stewardship, legacy, intergenerational wealth transfer, and intergenerational beneficence (Wiepking et al., 2012; Routley et al., 2017).

Wills are unique in that they can also be changed until the donor’s last breath, making maintaining the donor’s relationship and commitment difficult (Routley & Sargeant, 2017; Wiepking et al., 2012). And legacy gift is seen to be the last consumer decision of ultimate disposition, to be made at the end of life (Price et al., 2000). Donors also do not live to see the efficacy and impact of their gift (Routley et al., 2017).

This leads to some very rational self-oriented motivation which also applies to general giving but on a deeper level of intent, importance, relevance, and gravity, with regards to charitable bequest which we will examine below.

RATIONAL DRIVERS AND CONSIDERATIONS IN BEQUEST MAKING

Will-Making, Making Charitable Bequests

Charitable bequests are singular in approach in their need to first be activated by a will and only come to pass when a person is deceased. Barriers to the will-making and charitable bequest of uncertainty about the breadwinner’s lifetime, increasing health care costs and longevity-dependent children, and perceived lack of personal ability to make a financial impact (Routley & Sargeant, 2017; Chang, 2004; Palumbo,1999). Wills can also be changed until the donor’s last breath, making maintaining the donor’s relationship and commitment difficult. (Routley & Sargeant, 2017; Wiepking et al., 2012), and legacy gift is seen to be the last consumer decision of ultimate disposition, to be made at the end of life (Price et al., 2000).

Charitable bequests are typically considered in conjunction with making of will. Triggers to will-making are typically mortality-driven or changes in family or wealth structure (James, 2013). These include marriage, children, retirement, changes in life stage, being widowed, purchasing a house, going on long-distance travel, and difficulties in estate matters with family members (Rawlinson, 2004; Routley et al., 2017). Will-making is perceived to be aiding one’s preparation and reconciliation of one’s eventual demise from this physical body and life and having some form of immortality. (Bryant & Snizek, 1975). Demographically, age, wealth and education increase the probability of making a will (Routley et al., 2017).

Efficacy, Trust, Solicitation, and Organisational Factors

The efficacy of charitable organizations is requisite for leaving a bequest, as the deceased donor has no control over the enactment of the gift and they do not live to get to see its impact (Wiepking et al., 2012; Routley et al, 2012) They seek reassurance that their contribution will truly make a different to the organisation and benefit those in need, through efficient and effective resource usage, and in line with their intentions (Bekker and Wiepking, 2012; Bekkers, 2006; Bowman, 2004; Cheun and Chan, 2000; Sargeant et al., 2006).

In accordance with their needs to achieve symbolic immortality and preservation of self-image, values and self-concept, donors demonstrate a need for gifts to be spent wisely for the greater good, and its impact, otherwise, the donors may not be able to achieve their goals of reflecting the belief of self-efficacy and the ghost of their spirit living on (Routley & Sargeant 2014; Gecas,1989). Thus, practical initiates with direct and certain impacts like helping the elderly are sometimes preferred over longer-term future strategic initiatives like environmental sustainability (Routley & Sargeant 2014). Chang et al. (1999) also found that people who believed in the efficacy of charitable organisations are more inclined to charitable bequests.

Trust is another important motivator of charitable bequest. The social exchange theory is the theoretical foundation for the generation of trust, especially in relationship marketing (Hon and Grunig,1999; Waters, 2011). In general, inter vivos giving, trust leads to recurring donation and commitment and social trust and social network factors significantly predict the likelihood of being a giver. (Sargeant & Lee, 2004; Herzog & Yang, 2018), in a charitable bequest, legacy pledgers are even more demanding about professionalism, responsiveness, transparency and communications quality than other categories of donors (Pharoah & Harrow, 2009; Sargaent & Hilton, 2005). Potential donors expect transparent and regular communications, as well as voluntary disclosure of information to gain their trust (Saxton et al., 2014). Getting the endorsement of a high-status person is also seen to be trust and legitimized legacy giving (Bekkers & Wiepking 2011).

Cost and Benefit, Tax, Income, and Assets

Pragmatism and prudence rule the roost, charity also begins at home. One first needs to have enough financial resources and assets to leave a substantial charitable bequest and perceive the self as financially secure to share and distribute resources (Wiepking et al., 2012). Perception of not having the financial capacity to make a difference affects charitable bequest-making negatively (Wiepking et al., 2012). There is a phenomenon of “psychic poverty, where even people who are objectively well off can still feel financially insecure (Schervish and Havens, 2003; Sprinkel, 2009), with feelings of retention and inadequacies (Wiepking and Breeze, 2012).

Objectively, being more financially secure increases the probability of leaving a charitable bequest (Wiepking et al., 2012). Having already accounted for family also increases the probability of a charitable legacy (Wiepking et al., 2012). Children are the natural heirs and most common beneficiaries (Routley & Sargeant, 2014). In Hamilton’s (1964) inclusive fitness theory, people leave estates to relatives of closer genetic relations to ensure evolutionary success, as part of personal immortality (Paek et al., 2024). Gifting legacy to relations also signifies care, love and familial bonds (Routley & Sargeant, 2014).

Different types of inheritance reflecting the parent’s mindset and needs also affect the desire for a charitable bequest (Masson & Pestieau,1997; Routley & Sargeant, 2017). When the centre of focus of bequest is either exclusively on the parent needs as in exchange bequest, and accidental bequest, or purely on the child’s needs, the share of mind and share of wallet for charitable bequest may be low. In the instance of accidental bequest where no intention of parents in leaving wealth to children as they are concerned with their precautionary savings and deferred consumption, and children inherit only because their parents did not happen to live as long as they had expected to and had not invested their savings in a life annuity (Masson & Pestieau, 1997) the charitable bequest will not be a consideration. In an altruistic bequest where parents consider children’s preferences while anticipating their income and future needs either through the human capital transfer of education or non-human capital transfer of financial wealth (Masson & Pestieau, 1997) or in exchange bequest where parents promise inheritance in exchange for care as old age security (Masson & Pestieau, 1997) a charitable bequest may also not be top of mind.

These dynamics may take precedence over the role of actual wealth or income in motivating bequest-making. Wiepking et al., (2012) found no effect of the level of family assets on bequest making. In fact, contrary to expectations, people with lower incomes have a higher probability of making charitable bequests than lower incomes. Similarly, Sanders & Smith (2014) found no effect of wealth on charitable bequests (Sanders & Smith, 2014).

Another trigger to legacy gifts is the avoidance of inheritance tax (Sanders & Smith, 2014; Routley et al., 2017). Vandevelde (1997) critiqued inheritance tax as a motive that threatens the value of giving and also perpetual saving. Tax avoidance was a motivation for bequest pledgers who believed their money would be better spent by not-for-profits than the government (Sanders & Smith, 2014; Routley et al., 2017).

Intentions in Intergenerational Decision-Making

Bequest giving has an element of uncertainty in it. When people are unfamiliar, they tend to use previous behaviours as a point of reference. Specifically, people look to previous generations’ intentions to guide their own decisions for allocating resources for future generations (Bang et al., 2017). Norms and values are established by a group’s past (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Knowing how previous generations have gifted (or not) bequests, guides intergenerational beneficence (Bang et al., 2017). Intentions are also a more powerful driver than outcomes for charitable requests, and intentions matter more than payoffs (Charness & Levine, 2007; Rabin, 1993). This applies to charitable giving too (Bang et al., 2017). Even in the event of a bad outcome, salient information about the intended generosity of past generations still encourages consideration of charitable bequests (Bank et al., 2017).

FEAR OF DEATH AND GENERATIVITY THEORY

Fear of Death

Humans are driven by fear of death, and the perception that death only occurs at older ages. Unknown aspects of death and dying cause anxiety and self-efficacy beliefs help empower control to reduce death anxiety (Fry, 2003; Routley & Sargeant, 2014; Routley et al., 2017; Bang et al., 2017).

Becker (1973) in his seminal work The Denial of Death states the preoccupation of human activities & our unconscious strive to be “heroic” in avoiding, ignoring or defeating death. There are many reasons to fear death from grieving the loss of self-concept (Perkins, 1981), and self-image, especially resulting from bodily disabilities with ageing (Shaffer, 1970) to attachments to loved ones, loneliness (Routley et al., 2017), and the unknown which drive substantial “death anxiety”. Fromm (1947) identified perceived failure of not having lived or achieved what one has wanted as a major thrust for inciting fear of death. This fear of death also leads to an avoidance of will-making. Moreover, the intestacy of will-making is also tied to equating one’s self-worth and monetary worth, and money used to keep death away (Feldman,1952; Routley et al., 2017); disposal of wealth can be traumatic (Davis, 1990).

The desire for immortality has been one of the most significant activities as we age. We seek to master death by ensuring evolutionary success in Hamilton’s (1964) inclusive fitness theory. To give their offspring a heads up in the best financial position for future success, inheritance estates are typically left to those with close family and relatives with blood ties (Paek et al., 2024; Hamilton, 1964; Routley et al., 2017).

Transcending Death, Generativity Theory, Legacy Giving: The Immortal Elixir

Terror Management Theory by psychologists Greenberg, Solomon, and Pyszczynsk (2015) reflect how we manage our mortality by first avoidance, then desiring to conquer it with symbolic immortality. This transcending of death occurs when we acquire the knowledge of death has been described by Lifton (1979) as ‘man’s evolutionary leap’, as he ascribes knowledge of death as central to human experience.

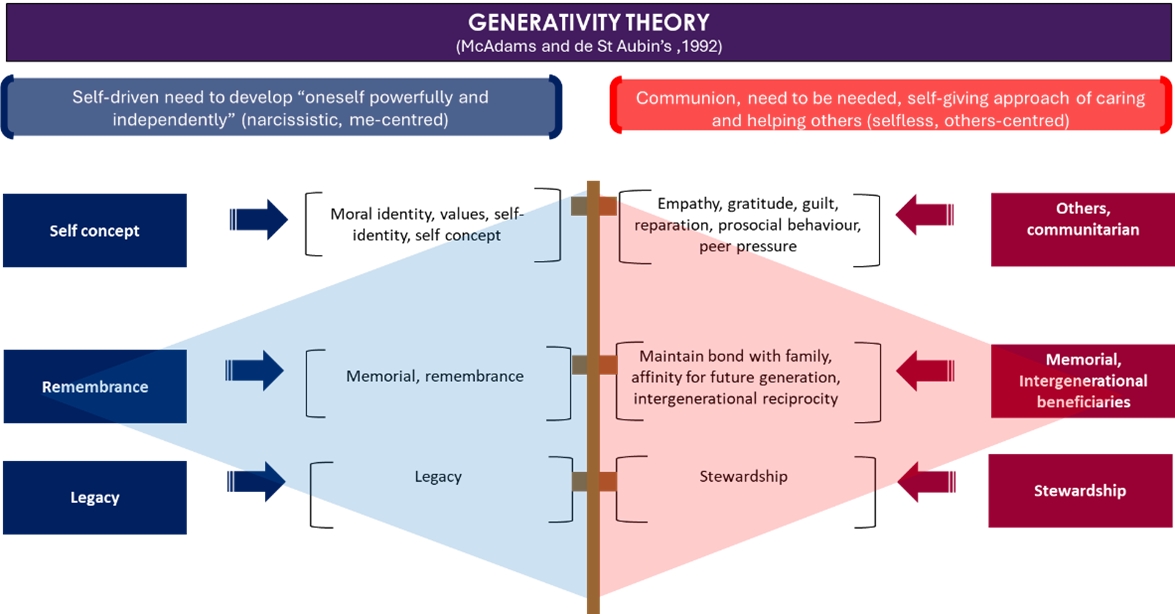

These ideas of self-preservation, immortality, and transcending death are captured in the concept of generativity defined by Kotre (1996, p. 10) as “a desire to invest one’s substance in forms of life and work that will outlive the self.” In a similar thread, McAdams and de St Aubin’s (1992) generativity theory states that how generativity is driven by both cultural demand and inner desire, in one’s personal life story, and the inner desire is motivated by two drivers of a more self-centred symbolic immortality vs. a more need to be needed, communion aspect.

To overcome the existential crisis, people seek to extend their presence on earth, a form of immortalising self by living a legacy through charitable bequests (Kotre, 1984, 1999; Bang et al., 2017). Thinking about and enacting legacy giving is empowering. Whilst death has a typical negative connotation, leaving a legacy is perceived to be a positive act of self-efficacy in enabling one’s belief and through it to bring good to others, to “play God” and impact the lives of others (Routley, et al., 2017; Routley & Sargeant, 2015; Gecas, 1989). It also has a sense of doing what you cannot complete in a lifetime which requires your death to complete it.

Applying the generativity theory to charitable bequest, we need to further understand two dimensions within the inner desire of seeking symbolic immortality through a self-driven need to develop “oneself powerfully and independently”, vs. a communion, need to be needed, self-giving approach of caring and helping others. Regardless of intentions, the characteristics of legacies are paradoxical; it requires one to be narcissistic to create a bequest that reflects one’s self-preservation, yet its outcome is centred on others, in providing aid and help (Rubinstein, 1996, p. 59) like a selfish heart, made pure. See schematic -Figure 1.

Figure 1: Generativity Theory

GENERATIVITY THEORY: SYMBOLIC IMMORTALITY

Symbolic Immortality – Self-Concept (Self-Identity, Moral Identity, Values)

In general donor behaviour literature, giving is often associated with one’s desire to portray a self-image of being an altruistic, empathic, socially responsible, agreeable, morally just or influential person (Bekker & Wiepking, 2011).

The preservation of self-concept and self-image is an important aspect of self-continuity and symbolic immortality to drive legacy giving (Routley et al., 2017; Bluck, et al., 2010 Hunter, 2008). Personal identity reflects the personal traits, character, and goals of the person and is a more powerful predictor of giving than social identity (Aaker & Akutsu, 2009). The dual nature of legacy-giving with self vs. others orientation may also be reflected in their self-construal. Interdependent orientation, for example, being attached to maintain kin ties and providing for them fosters stronger commitments to aid in-group than out-group members (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Fajardo et.al., 2018). In contrast, when a donor giver exhibits an independent self-construal, they may demonstrate similar propensities to help needy in-group and out-group others e.g. once decided on legacy-making, the outcome results in benefits for others (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Fajardo et.al., 2018).

In the quest for immortality, legacy givers may seek to connect their future selves with groups, charities and future generations to maintain their self-concept (Wade-Benzoni, 2019). Identification with an organization’s values can help alleviate death fears (Routley & Sargeant, 2014). Through bequest giving, the individual can extend themselves into a post-death future, to preserve or commemorate the values they hold and the people or experiences that shaped them (Routley & Sargeant, 2014).

People seek consistency in their beliefs and actions, and these are demonstrated through the values they hold (Wiepking et al., 2012; Easwar and Kashyap, 2009; Routley et al., 2017 Reed et al., 2007; Fajardo et.al., 2018; Winterich et al., 2012). The values that drive charitable giving, include altruistic values (Bekkers & Schuyt, 2008; Farmer& Fedor, 2001; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011; Reed et al., 2007; Fajardo et.al., 2018; Winterich et al., 2012; James III, 2009a; Madden and Scaife, 2008b; Routley et al., 2007; Sargeant et al., 2006a; Schervish and Havens, 2003); feel socially responsible and motivated to make the world a better place. (Weerts & Ronca, 2007; Amato,1985; Reed & Selbee, 2002; Schuyt, Smit, & Bekkers, 2010; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011); prosocial values with less materialistic goals (Sargeant et al., 2000; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2006); adopt a moral principle of care (Schervish & Havens, 2002; Wilhelm & Bekkers, 2010, Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011); care about social order and social justice (Todd & Lawson, 1999; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011); political and religious values (Wiekping et al. 2012; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011).

The adherence to values is closely knitted to one’s moral identity (Shang & Reed, 2008; Routley et al., 2017). Moral identities are important to drive donors. Being recognised for their internalised moral identity and high external symbolism of moral identity enhances giving. (Cui., et al, 2021; Winterich et al., 2012). Appealing to one’s sense of self and moral identity drives donations (Shang & Reed, 2008). The need to maintain a moral self-concept even encourages higher donations to faraway causes (Xu et al.,2020; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Increased commitment to moral identity increases social well-being (Cui., et al, 2021).

Values and moral identity are important constructs of self-concept. Legacy donors either identify themselves with the community or through shared values with the recipient nonprofit (Routley & Sargeant, 2017; Sargeant & Shang, 2008). Legacy giving motivated by identification may decrease death anxiety as it increases belief in self-efficacy through self-empowerment and self-control (Routley & Sargeant, 2014; Fry, 2003), and the enduring nature of organisations elevates self-esteem (Sargeant and Shang, 2008).

Findings on the role of religious values on charitable requests and legacy are mixed. Wiekping et al., 2012 found that religious values do not drive charitable bequests, in line with Norenzayan and Shariff (2008). Compared to religious value motivating general charitable giving (Bekkers and Schuyt, 2008; Hoge and Yang, 1994; Wiekping, et al., 2014), bequests are less conspicuous and may not drive prosocial behaviour as the reward of a positive in-group reputation is less forthcoming (Norenzayan and Shariff, 2008).

Compared to general charitable giving, religious values are less likely to drive charitable bequest (Norenzayan and Shariff, 2008). Religious value motivates general charitable giving (Bekkers and Schuyt, 2008; Hoge and Yang, 1994; Wiekping, et al., 2014), even if church membership is on the decline, religious giving is rising. People are triggered by seeking an afterlife (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011) and connecting with church social networks (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011b; Bennett, 2006; Herzog & Yang, 2018; Wiepking & Maas, 2009). However, religious values do not drive charitable bequests as bequests are less conspicuous and may not drive prosocial behaviour as the reward of a positive in-group reputation is less forthcoming (Norenzayan and Shariff, 2008; Wiepking et al., 2012).

Symbolic Immortality – Remembrance (Memorial, Reminiscence)

Forgetfulness and the fear of being forgotten. St John Cross said, “At the evening of love, we will be judged only by love.” How do we want to be remembered? This is a time-tested concept. Death is the natural full stop and challenges the individual identity most significantly. The will represents the ultimate disposition and consumer decision (Unruh, 1983). In this context to obtain symbolic immortality, contrary to conventional thinking, disposition is not about losing the identities one wants to dispose of, but rather about identifying those that the individual would like to be remembered for (Unruh, 1983).

A 17th-century document on wills documents the ego need of charitable bequest pledgers. Giving to charity is a conduit to form and preserve how they want to be remembered by society and their families (Routley et al., 2017; McGranahan, 2000). They make meaning through objects and possessions owned, and passing this down is a way to commemorate, preserve memory and trigger reminiscence of their lives (Routley et al., 2017). In this driver of symbolic immortality through memorial and remembrance, many things from families to charities fight for the donor’s share of memory (Routley & Sargeant, 2014). Both money (Feldman, 1952) and possessions have been described as providing a form of protection from death and provide “immortality value” (Turley, 2005). The legacy bequest creates a form of autobiographical memory which serves to transfer individual identity and family values (Price et al, 2000; Curasi et al, 2004; Curasi, 2011; Routley et al., 2017; Routley and Sargeant, 2015; James & O’Boyle, 2012). It is only through death and its legacy left behind that their life is complete.

Symbolic Immortality – Legacy

Legacy is defined as an enduring meaning attached to one’s identity and manifested in the impact that one has on others beyond the temporal constraint of the lifespan (Fox, Tost, & Wade-Benzoni, 2010; Bang et al., 2017). Leaving a legacy requires one to find meaning in their life and create a narrative that perpetuates one’s existence (Becker, 1973; Kotre, 1984; Routley et al., 2017). In creating a legacy, people seek positive self-promotion by providing a better future for the next generation (Newton et al., 2014).

There are four types of legacies. Hunter and Rowles (2005) identified biological, material and value legacies. Biological legacy comprises genetic, health, and body make-up; material legacy is about the pursuit of heirlooms, possessions, and symbols; the legacy of values may be personal, social, or cultural values. Values are present in each type of legacy and show the transference of one’s values and beliefs to others (Bang et al., 2017; Newton et al., 2014). Humans have a natural desire to regenerate. In the concept of secular immortality where one consciously curates a social legacy for symbolic immortality, Hirschman (1990) states that mere wealth is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for social prominence. Individuals actively work on building a social legacy where the family name is entrenched in society for philanthropy and works of public service. This need to live on expressed as a family and is deemed a more important driver to charitable bequest than an individual need or tax drivers (Sargeant et. al.,2006). One study on childless women also found them beset with sadness and despair when reflecting on having no descendants to make a request (Rubinstein, 1996).

Legacy giving is seen to be a positive activity that overcomes the negative emotions of death, and also an empowerment of self-continuation in symbolic immorality. It is a good mechanism in part of death education to reduce death anxiety (Sligte et.al., 2013).

GENERATIVITY THEORY: OTHERS-COMMUNION

The second aspect of McAdams and de St Aubin’s (1992) generativity theory is the need to be needed, an others-centred, communitarian approach to achieve symbolic immortality. It corresponds with a desire to relate to others in loving and caring ways (McAdams & de St Aubin, 1992).

Communion – Others, Communitarian (Empathy and Gratitude)

Many legacy supporters are motivated by reciprocity, or the need to give something back, perhaps because their life has been touched by the cause or the organisation (Sargeant and Hilton, 2005; Routley et al., 2017). Both emotions of empathy and gratitude are ignited. For example, in medical research, this sense of being part of a community of participation is observed in individuals who have been afflicted with ailments and experienced the care of the medical system and are more likely to leave a bequest than non-sufferers (Schervish, 1993, 1997). Gratitude and desire to reciprocate – Service users who may feel that they should donate to give something back in return for the services offered. – Legacies offer donors a unique opportunity to thank service providers for their assistance, by giving something back in return for the service and care rendered (Bruce, 1998; Radcliffe, 2002; Smee & Ford, 2003; Routley et al., 2017). This driver of reciprocity and gratitude is also what differentiates legacy givers from donors in general (Routley et al., 2017).

Legacy pledgers tend to identify strongly with the causes they support. The charities donors choose to support are typically linked to the experience of self or family member, and they want to spare someone else the same suffering of what was endured or simply seek to improve the lives of others (Sargeant & Hilton,2005; Routley et al., 2017). These personal experiences or significant life events impart a sense of empathy to the giver (Routley & Sargeant, 2014) and such motivated giving satisfies a desire to show gratitude (Bekker & Wiepking, 2011). Empathy encompasses a sense of connectedness and intimacy and may be defined as an individual’s emotional arousal elicited by the expression of emotion in another (Routley et al., 2017; Alea & Bluck, 2007; Berger, 1962; Shelton and Rogers, 1981; Eisenberg and Miller, 1987).

In donor-giving literature, there are two types of empathy: selfless or ego-helping (Kumar & Chakrabarti, 2023; Batson et al., 1987; Verhaert & Van den Poel, 2011, Bendapudi et al., 1996; Wiepking & Maas, 2009). Ego-helping empathy is self-oriented and seeks to make oneself feel better by giving. The outcome is the “warm glow”, the joy of giving (Andreoni, 1989) is a form of impure altruism. “Helping others produces positive psychological consequences for the helper, “empathic joy” in economic models of philanthropy. Recent evidence from neuropsychological studies suggests that charity donations “elicit neural activity in areas linked to reward processing” (Harbaugh et al., 2007). In contrast, self-less empathy makes no demands.

Communion – Others, Communitarian (Guilt and Reparation)

Guilt and reparations are triggers to charity bequests. People give to reduce guilt, and negative feelings and avoid punishments (Bekker & Wiepking, 2011; Routley et al., 2017; Kidd & Berkowitz, 1976; Cialdini et al., 1982; Cialdini et al., 1987; Sargent and Hilton 2005). Social responsibility and moral guilt are two of four types of consumer guilt (Burnett & Lunsford,1994). Donors are seen to derive utility from personal mood management or negative state relief. However, legacy pledgers have less need for negative state relief than other categories of donors (Routley et al., 2017).

Empathy also increases recognition of guilt. (Basil et al., 2008; Urbonavicius et al., 2019; Andreoni et al., 2017; Hibbert et al. 2007) and legacy giving reduces this and portrays one to be a morally just person (Bekker & Wiepking, 2011). Guilt increases in the presence of others and triggers one to be prosocial (Basil et al., 2008), and guilt and donation behaviour is impacted by agent and persuasion knowledge (Hibbert et al. 2007).

Experiments on helping behaviour show that assisting others may be an effective way of repairing one’s self-image after one has harmed another (Carlsmith & Gross, 1969; Freedman, Wallington, & Bless, 1967; Regan, Williams, & Sparling, 1972). One study tested the guilt hypothesis by comparing donations among people entering a church during confession hours and people leaving the church after confession when their guilt had been reduced (Harris, Benson, & Hall, 1975).

Communion – Others, Communitarian (Prosocial Behaviour, Entitativity, Peer Pressure and Social Norm)

In the Theory of Reasoned Action (Cicirelli, 1998; Blanchard-Fields, 1997; Warburton and Terry, 2000; Hirschman,1990, p. 32). This theory guides how we make decisions when faced with unfamiliar situations. Will-making will be unfamiliar to most people and coping strategies will include seeking the views of others, especially older. Advice may come from relationships with a representative of a charity, encouragement of family and friends, or encouragement of legal and financial advisors (Sargeant & Hilton, 2005).

People are driven by social norms and pressure. The model of conformity postulates that individuals care about how others perceive them and strive to behave within social norms (Bernheim, 2002). Moreover, individuals are influenced not only by the perceived views of others but also by the behaviour of others (Warburton and Terry, 2000).

Going beyond guilt and reparations, On the other of the coin, legacy giving also helps the giver feel good for being in line with social norms (Bekker & Wiekping, 2011).

In an experiment, Sanders & Smith (2014) found that a “strong ask” in which the lawyer additionally suggests that leaving money is a social norm and prompts the will-maker to think about a cause that they feel passionate about, increases the power of the ask. In shaping the response to fundraising requests, charities may show evidence of societal norms in giving to encourage them to leave a bequest (Routley & Sargeant, 2017; Sanders & Smith, 2014).

Social connections and networks are a part of life and key to contributing to an older person’s sense of self-worth, security, and social competence (Routley et al., 2017). Social contacts with fundraisers provide a form of interaction and connection for the elderly (Routley et al., 2017) One may even build a lifestyle around charitable bequest for older people. Social contacts with fundraisers, social interaction experiences through social activities, the honouring of donors, or volunteer work (or, in the case of legacy fundraising, membership of a society) may substitute for previous relationships of a more intimate nature (Routley et al., 2017).

Such movements in communities may also result in entitativity, a form of communitarianism which refers to the degree to which a collection of individuals comprises a single coherent entity for increased solidarity (Vandevelde, 1997). Campbell (1958) theorized about the nature of groupness, which he called entitativity. Entitativity may play a role in a solicitation drive by a charity. The high-entitativity groups of positively valanced victims receive roughly twice the donations as the low entitativity groups (Smith et al., 2013; Fajardo, et al., 2018).

Attitude and subjective norms are also significant predictors of inclinations to donate money. Social norms have powerful social influences on human behaviours, and individuals attempt compliance with these social norms, which commonly act as a driver for pro-social behaviour (Cialdini, 2007; Festinger, 1954; Goldstein et al., 2008; Konkoly and Perloff, 1990; Bénabou & Tirole, 2006). With prosocial behaviour motivation in charitable bequest – people sometimes pass along their financial resources to unrelated future others, donating to the greater good even at the personal expense of their consumption (Zaval et al., 2015; Paek et al. 2024).

Sharing of social information which involves sharing the stories of living and deceased legacy pledgers with potential legacy donors in communication and solicitation is a key driver to legacy pledges. James and Routley (2016) found that groups exposed to the stories reported significantly greater interest in leaving a legacy, relative to their initial interest in making a lifetime gift than did the control group. In addition, they found that living donor stories were consistently more effective than deceased donor stories at increasing the relative interest in making a bequest gift. Information on significant contributions from others influences a donor to contribute. Social norms can have a significant impact on casual decisions to donate (Shang & Croson, 2009; Bennett & Ali-Choudhury, 2009). This is also in line with the theory of reasoned action where access to social information provides reassurance.

Communion – Memorial (Maintain Bonds With Family)

Wade-Benzoni and Tost (2009) in the area of intergenerational behaviour indicate the importance of preserving family relations, noting that the desire to affiliate with others is a frequent reaction to mortality salience. People seek to preserve a good post-death self-image for the family, a lasting memorial for self or others, to preserve family harmony and to be well thought of (Wade-Benzoni & Tost,2009; Routley et al., 2017).

Legacy bequest helps to fulfil the need to maintain bonds, continual nurturing of love and reiterate kinship in identity with loved ones (Routley & Sargeant, 2014). Charitable gifts can also express the bond by supporting charities that help an afflicted loved one (James,2015). People also make memorial bequests in memory of loved ones. Some 33% of US bequestors are motivated to leave a charitable bequest out of a desire to create a lasting memorial for themselves or a loved one (Wiekping et al., 2012; NCPG, 2001). ‘Warm’ In-Memory donors, are twice as likely to be legacy pledgers or prospects than other regular donors (Routley et al., 2017).

Charities could also encourage their supporters to think about the connections with a cause that has formed an important part of their life stories.

Communion – Intergenerational Beneficiaries (Affinity Future Generation, Intergenerational Reciprocity)

Legacy is a concept that has meaning only if a person’s behaviour has implications for other people in the future. When legacy motivations are enacted, intergenerational beneficence is increased (Wade-Benzoni, 2019). People seek to create an affinity with future generations (Bang et al., 2017) and to live on in them through impact and memory (Wade-Benzoni, 2019).

The desire to leave a positive legacy for the future also motivates intergenerational beneficence because it enables people to experience a meaningful connection with a social entity that will presumably outlive themselves (Bang et al., 2021) and people can achieve unity with an enduring future that extends beyond themselves (Kotre, 1984).

Wade-Benzoni (2019) fleshes out intergenerational reciprocity where people do not always have the opportunity to reciprocate the deeds of prior generations directly back to them, and the present generation often does not benefit from the sacrifices it makes for future generations. People could reciprocate others’ actions, not by directly rewarding their benefactors, but by passing on the benefits to future generations. (Wade-Benzoni, 2019). Intergenerational behaviour is more strongly influenced by the perceived intentions of prior generations as compared to the actual outcomes inherited (Bang et al., 2017).

This idea of atonement and reparations is especially triggered when the preceding generation had selfish intentions, current-generation decision-makers may gravitate towards legacy motivations against negative forward reciprocation, to circumvent their predecessors’ transgressions and offset the effects of past wrongs (Bang et al., 2017).

The notion of shame and guilt of having derived benefits from profits and enjoyable activities whilst allocating the burdens of debt, hazardous waste and climate changes heightens ethical concerns and intensifies moral emotions to feel responsible for future generations (Bang et al., 2017; Wade-Benzoni et al. 2017). This making of reparations drives affinity with future generations and integrational reciprocity to legacy-giving for intergenerational beneficiaries (Zaval et al., 2015; Wade-Benzoni et al., 2010; Hernandez, 2012; Wade-Benzoni et al., 2008), and also break patterns of perpetuating oppressions overtime (Bang et al., 2017).

Communion – Stewardship

Legacy and stewardship, although distinct constructs, play an interrelated role in the intergenerational story. Stewardship is the extent to which an individual willingly subjugates his or her interests to act in the protection of others’ long-term welfare. individuals value actions that benefit the long-term welfare of others and are guided in their behaviour by this “other-regarding” perspective and long-term orientation (Hernandez, 2012).

Good begets good. The past generation’s good intentions lead to more generous behaviour in the present generation due to stewardship. (Bang et al, 2017) Past stewardship behaviours of others will positively influence individuals’ sense of retrospective obligation, and eventually, this process can generate a norm of beneficent intergenerational reciprocity (Hernandez, 2012). Hernandez (2012) found knowing past generosity is causal in activating feelings of responsibility and other-oriented mindsets.

As we live in a world of scarce resources, as well as the dichotomy of managing one’s desires vs leading an others-centred life, people must make trade-offs between the interests of present and future generations. In the psychology of intergenerational decision-making (Bang et al., 2017) and studies in “intergenerational dilemmas” focused on identifying psychological features of intergenerational decisions, barriers to advancing intergenerational beneficence, and variables that lead the present generation to act generously on behalf of future others (Wade-Benzoni & Tost, 2009). Bang et al., (2017) found that people use the preceding generation’s intentions as a determinant of the present and the future. The transparency of past intergenerational decisions may nudge the current generation to consider its responsibility in caring for the future.

Barriers to acting on behalf of future generations are mainly self-centred and include discounting the value of resources to be consumed by future others (Wade-Benzoni, 2008); Individuals typically prefer smaller sooner rewards over larger-later rewards and are less likely to choose an option that benefits others rather than themselves (Bang et al., 2017); lack of direct reciprocity of future generations prevents people from sacrificing own gains for the good of future (Care, 1982). Moreover, when memories are not healed, one may also choose to pass on the burdens and sufferings to the next generation as retaliation for the bad received from past generations (Wade-Benzoni,2002).

As critical issues in society today involve long time horizons and multiple generations of people. In intergeneration decisions, the interests of the present and future generations may not be aligned. (Wade-Benzoni, 2019). One of the challenges to enacting legacy giving is that making a will is typically not performed earlier on in life. This time delay in psychological distance may be consequential in the intergenerational decision with more integrational discounting and fewer people advocating for the benefit of future generations (Wade-Benzoni, 2019).

Charities may want to influence the pipeline to enact legacy motivation earlier on (Wade-Benzoni, 2003). In uncertainty, both power priming and greater levels of uncertainty about the future consequences of present decisions can elicit stewardship attitudes, which in turn temper self-interested behaviour on the part of the preceding generation (Wade-Benzoni et al., 2008; Wade-Benzoni, 2019). Nudging for legacy motivations promotes stewardship to result in intergeneration beneficence when the presence of past good intentions has not been sufficiently enacted (Bang et al., 2017). In communication and outreach for a charitable bequest, to effectively imbue intergenerational responsibility, it will be important to know the behavioural norm of the preceding generation to motivate and guide people to more morally responsible actions toward future others (Hernandez, 2012; Bang et al., 2017).

Learn more about impact investing as an approach to sustainable investing in CSP SG’s Applied Sustainable Investing in Wealth Management courses, available at both a L3 (introductory) and L4 (intermediate) level. CSP Zurich also offers a Learning from Leading Impact Family Offices course designed to educate wealth holders on best practices to operationalise impact investing, in addition to an Impact Investing for the Next Generation course, that equips next generation members of ultra-high-net-worth families with the technical and soft skills needed to align their investments with their value.

References:

Aaker, J. L., & Akutsu, S. (2009). Why do people give? The role of identity in giving. Journal of consumer psychology, 19(3), 267-270.

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The economic journal, 100(401), 464-477.

Andreoni, J., Rao, J. M., & Trachtman, H. (2017). Avoiding the ask: A field experiment on altruism, empathy, and charitable giving. Journal of political Economy, 125(3), 625-653.

Bang, H. M., Koval, C. Z., & Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2017). It’s the thought that counts over time: The interplay of intent, outcome, stewardship, and legacy motivations in intergenerational reciprocity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 73, 197-210.

Basil, D. Z., Ridgway, N. M., & Basil, M. D. (2008). Guilt and giving: A process model of empathy and efficacy. Psychology & marketing, 25(1), 1-23.

Batson, C. D., Dyck, J. L., Brandt, J. R., Batson, J. G., Powell, A. L., McMaster, M. R., & Griffitt, C. (1988). Five studies testing two new egoistic alternatives to the empathy-altruism hypothesis. Journal of personality and social psychology, 55(1), 52.

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and voluntary sector quarterly, 40(5), 924-973.

Bendapudi, N., Singh, S. N., & Bendapudi, V. (1996). Enhancing helping behavior: An integrative framework for promotion planning. Journal of marketing, 60(3), 33-49.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and prosocial behavior. American economic review, 96(5), 1652-1678.

Carnegie, A. (1962). The gospel of wealth, and other timely essays. Harvard University Press.

Carlsmith, J. M., & Gross, A. E. (1969). Some effects of guilt on compliance. Journal of personality and social psychology, 11(3), 232.

Community Foundation Singapore. A Toolkit for Advisors, https://legacygiving.sg/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/A-Greater-Gift-Toolkit-for-Advisors_updated_v2.pdf

Community Foundation Annual report, 2023

Crimston, C. R., Bain, P. G., Hornsey, M. J., & Bastian, B. (2016). Moral expansiveness: Examining variability in the extension of the moral world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(4), 636.

Croson, R., & Shang, J. (2008). The impact of downward social information on contribution decisions. Experimental economics, 11, 221-233.

Cunliffe, J., & Erreygers, G. (Eds.). (2013). Inherited wealth, justice and equality. London: Routledge.

Exline, J. J., & Hill, P. C. (2012). Humility: A consistent and robust predictor of generosity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(3), 208-218.

Fajardo, T. M., Townsend, C., & Bolander, W. (2018). Toward an optimal donation solicitation: Evidence from the field of the differential influence of donor-related and organization-related information on donation choice and amount. Journal of Marketing, 82(2), 142-152.

Feliu, N., & Botero, I. C. (2016). Philanthropy in family enterprises: A review of literature. Family Business Review, 29(1), 121-141.

Fessler, P., & Schürz, M. (2020). Inheritance and equal opportunity–it is the family that matters. Public Sector Economics, 44(4), 463-482.

Freedman, J. L., Wallington, S. A., & Bless, E. (1967). Compliance without pressure: The effect of guilt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 7(2p1), 117.

Giving in the Netherlands 2020

Giving USA 2024 Report

Ghorbani, M., Liao, Y., Çayköylü, S., & Chand, M. (2013). Guilt, shame, and reparative behavior: The effect of psychological proximity. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 311-323.

Harris, M. B., Benson, S. M., & Hall, C. L. (1975). The effects of confession on altruism. The Journal of Social Psychology, 96(2), 187-192.

Hibbert, S., Smith, A., Davies, A., & Ireland, F. (2007). Guilt appeals: Persuasion knowledge and charitable giving. Psychology & Marketing, 24(8), 723-742.

Investor’s Guide to Impact Investing (CSP Zurich Publication)

10 ingredients to Impact investing (CSP Zurich Publication)

Kumar, A., & Chakrabarti, S. (2023). Charity donor behavior: a systematic literature review and research agenda. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 35(1), 1-46.

Masson, A., & Pestieau, P. (1997). Bequests motives and models of inheritance: a survey of the literature. Is inheritance legitimate? Ethical and economic aspects of wealth transfers, 54-88.

McAdams, D. P., & De St Aubin, E. (1992). A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 1003-1015.

Paek, J. J., Goya-Tocchetto, D., & Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2024). The Andrew Carnegie Effect: Legacy Motives Increase the Intergenerational Allocation of Wealth to Collective Causes. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 19485506231201684.

Population in brief, Prime Minister’s Office, 2023, Pg 10

Price, L. L., Arnould, E. J., & Folkman Curasi, C. (2000). Older consumers’ disposition of special possessions. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(2), 179-201.

Regan, D. T., Williams, M., & Sparling, S. (1972). Voluntary expiation of guilt: A field experiment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24(1), 42.

Routley, D. C., Sargeant, A., & Day, H. Everything We Know About Legacy Giving In 2017.

Routley, C., & Sargeant, A. (2015). Leaving a bequest: Living on through charitable gifts. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(5), 869-885.

Sanders, M., & Smith, S. (2014). A Warm Glow in the After Life?: The Determinants of Charitable Bequests. CMPO.

Sargeant, A., & Hilton, T. (2005). The final gift: targeting the potential charity legator. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 10(1), 3-16.

Sefton, M., & Steinberg, R. (1996). Reward structures in public good experiments. Journal of Public Economics, 61(2), 263-287.

Smith, J. R., Terry, D. J., Manstead, A. S., Louis, W. R., Kotterman, D., & Wolfs, J. (2008). The attitude–behavior relationship in consumer conduct: The role of norms, past behavior, and self-identity. The Journal of social psychology, 148(3), 311-334.

Urbonavicius, S., Adomaviciute, K., Urbutyte, I., & Cherian, J. (2019). Donation to charity and purchase of cause‐related products: The influence of existential guilt and experience. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 18(2), 89-96.

Vandevelde, T. (1997). Inheritance taxation, equal opportunities and the desire of immortality. In Is Inheritance Legitimate? Ethical and Economic Aspects of Wealth Transfers (pp. 1-15). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Walkate.H and F. Paetzold (2024) White paper: Impact Investing Grows Up: from Intentionality to Additionality

Wade-Benzoni, K. A., Sondak, H., & Galinsky, A. D. (2010). Leaving a legacy: Intergenerational allocations of benefits and burdens. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(1), 7-34.

Wade-Benzoni, K. A., & Tost, L. P. (2009). The egoism and altruism of intergenerational behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 165–193.

Wade-Benzoni, K. A., Sondak, H., & Galinsky, A. D. (2010). Leaving a legacy: Intergenerational allocations of benefits and burdens. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(1), 7-34

Wade-Benzoni, K. A., Tost, L. P., Hernandez, M., & Larrick, R. P. (2012). It’s only a matter of time: Death, legacies, and intergenerational decisions. Psychological Science, 23(7), 704-709.

Wiepking, P., Scaife, W., & McDonald, K. (2012). Motives and barriers to bequest giving. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11(1), 56-66.

Wiepking, P., & Maas, I. (2009). Resources that make you generous: Effects of social and human resources on charitable giving. Social Forces, 87(4), 1973-1995.

Wishart, R., & James III, R. N. (2021). The final outcome of charitable bequest gift intentions: Findings and implications for legacy fundraising. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 26(4), e1703.

Zaval, L., Markowitz, E. M., & Weber, E. U. (2015). How will I be remembered? Conserving the environment for the sake of one’s legacy. Psychological science, 26(2), 231-236.

Vandevelde, T. (1997). Inheritance taxation, equal opportunities and the desire of immortality. In Is Inheritance Legitimate? Ethical and Economic Aspects of Wealth Transfers (pp. 1-15). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Vasoo, S., Singh, B., & Chookkanathan, S. (Eds.). (2023). Singapore Ageing: Issues and Challenges Ahead.

Verhaert, G. A., & Van den Poel, D. (2011). Empathy as added value in predicting donation behavior. Journal of Business Research, 64(12), 1288-1295.

https://www.mas.gov.sg/schemes-and-initiatives/philanthropy-tax-incentive-scheme-for-family-offices